Das turbulente aber konstante Wirtschaftswachstum der Türkei seit den 1990er Jahren hat ihr Verhältnis zum Rest Europas neu definiert. Zeitgleich sind die 1990er Jahre Zeugen einer rasanten Entwicklung der zeitgenössischen türkischen Kunst, die machtvoll in den internationalen Fokus rückte und spätestens mit einer Vielzahl in den 2000er Jahren neu gegründeter Ausstellungshäuser ist Istanbul als Ort der zeitgenössischen Kunst heute international fest etabliert. Erben dieser Entwicklung sind Künstler, die sich in neuen Formen kritisch mit den Auswirkungen der gesellschaftlichen Veränderungen auseinandersetzen. Die Autorin Merve Ünsal über Nilbar Güreş, eine der wichtigsten türkischen Künstlerinnen dieser jüngeren Generation.

Nilbar Güreş’s works can perhaps best be defined as interventions; their relationship with the world disrupts a/their own narration and this disruption is precisely the material for her works. In other words, the artist positions her works—and herself, due to the self-reflexive nature of her practice—between things that are and things that could be. Güreş’s politically charged works are fragmented, producing diminutive accounts that are perhaps more representative and „truthful“ than major portrayals.

An acute observer, Güreş’s practice employs the slippage between the documentary and the fictional to produce an inherently ambiguious position, both as an author and as an individual, charging the works with a quotidian ideology that can be interpreted as a proposal of action for those of us who struggle with the same social, political, cultural hierarchies that threaten the individual’s integrity.

Open Phone Booth

One of Nilbar Güreş’s most recent projects, Open Phone Booth, is revealing of what could be dubbed the artist’s spontaneous, daily politics. Open Phone Booth is based on the artist’s research in the Kurdish Alevi village in Bingöl, a city in Eastern Turkey. The photography-based work was first shown in Frieze Frame in 2011 and the artist considers the project as in-progress. The work is essentially rooted in this village’s reality; if the conditions shift, the work will shift. Each exhibition of the work is both a response to the time and a record of what Güreş has been observing in this village for most of her life.

ALİŞAN IS CALLING, from the series Open Phone Booth, 2011 C-print, 52 x 72 cm (framed)

Still Life-1, from the series Open Phone Booth, C-print, 50 x 70 cm

It is important at this point to situate Bingöl in the context of the politics of the Republic of Turkey in the last thirty years as well as in Güreş’s personal history. Bingöl is located in the southeastern part of Turkey, an area that has been plagued by armed conflict.

In 1984, PKK [Kurdish Workers‘ Party] made official their movement to establish independent Kurdistan. Adnan Yildiz, in his article on this project, cites 46 declarations of state of emergency in this region between 1982 and 2012. Bingöl is thus located both in and outside of Turkey; the heterotopia of Bingöl, and specifically this village, hold within everything that is outside while the inside is governed by rules and conditions that are removed from the outside. Güreş’s familiarity stems from a most intimate relationship as her father is from here.

The village, one of the nine Alevi villages in Bingöl and many more that belong to other cities in Eastern Turkey—is both Kurdish and Alevi, ethnic and religious minorities, respectively. These villages remain outside of the state’s infrastructural reach. Promised infrastructure that the villagers have requested and paid for never made it to the village. The doubly „minor“ population of the village is left suspended in this peculiar territory of belonging without the benefits of belonging.

The very basic privileges of being a part of a by-now prospering state seems to be deferred, when identities, ideologies, and geographies diverge. The state’s specific „insufficiency“ for the populations in question is a form of discrimination is that is made easy by the geographic conditions of the region and the distance from major cities such as Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir, and Adana, while the contrast between neighboring villages exposes the idiosyncrasies of a state that is anything but weak, in areas and situations that are aligned with the current political authority.

Open Phone Booth’s constituents include constructed scenes of people interacting, individual portraits, still lives of both what Güreş found and what she suggests she could have found, a three-channel video, the readymade of a phone pole.

POLE THAT IS TO SAY SCULPTURE-1, from the series Open Phone Booth, 2011 C-print, 52 x 72 cm (framed)

The phone pole that was erected years ago is a lonely monument to the absence of what could potentially make life „normal“ in this village. Without any other poles or phone lines to connect the poles, the pole serves as a testament to the absurdity of the quotidian life here. The exposed lack of something creates a tension that lurks under the surface of the images. This is precisely where the works claim some authority that is humbled by what is being witnessed while also being offered as an unpresuming solution that could potentially make a difference.

Güreş’s mixture of documenting what she sees—in the images of the phone pole and of villagers outside to find the best signal for their cell phones and connect with loved ones far away—and creating what she observes through still lifes—in the image of the phone buried in the snow and of the plumbing in the middle of a flowing body of water—precisely, humorously, gently identify the self-empowering, self-organizing nature of the individual.

While Güreş’s personal relationship with the village helps explain her intimate relationship with the place, Open Phone Booth goes beyond a family story: in the artist’s improvised research methods and combination of various strategies, as if to test out what would work best and then using all of her unfinished tests to stitch together a story that was both self-contained and gave references to the reality of the village.

Güreş integrates strategies of documentation, fiction, and performance in a seamless web of images, images of actions and images of acts. Güreş’s distinctive juxtaposition of different media, approaches, and sensibilities can also be seen in her earlier body of work, TrabZONE (2010).

Trapzone

Perhaps not coincidentally, TrabZONE is also deeply entrenched in Güreş’s memory, as her grandmother is from Trabzon, a city in the northern part of Turkey, in the Black Sea region. Güreş’s matriarchal relationship with the city informs her photography-based works in the series, in which Güreş interrogates various dimensions of female identity, in the specific context of this city. The tensions, confessions, and identifications, produced in the images in a most sincere manner, invite the viewer to an experience that is deceptively fictional. In other words, the fictional world that Güreş has created in the TrabZONE series is so deeply rooted in the artist’s observations and perceptions of her childhood that the fictional world has become somewhat more real than other expressions of familiar concepts such as conservativeness and gender divides.

The women in Güreş’s images desire each other in the most unexpected locale of the mosque, two become one through a scarf that is taut yet intact, they literally cover each other to conceal, and house chores do not require any effort any more.

THE GRAPES, from the series TrabZONE, 2010 C-print, 103 x 152 cm

In the larger context of Güreş’s practice, it is thus possible to read TrabZONE as a prelude to Open Phone Booth for not only formal reasons, but also for reasons of scale. TrabZONE—an reinterpretation—fictionalizes that she knows to comment on the place from the position of a woman. This woman has a permeable relationship with the place as she has been able to not participate in the daily life that governs and perpetuates the conditions of the women.

On the other hand, Open Phone Booth is a more genderless, political story that is of a much smaller place. While TrabZONE confronts the viewer with the women that we know, Open Phone Booth is a portrayal of a place that most choose not to know. The levels of „expose“ differentiate the two bodies of work, pointing to the common usage of forms of construction that can be constantly re-negotiated to reveal the new and the old, the familiar and the unfamiliar.

PATTERN, from the series TrabZONE, 2010

C-print, diptych, 103 x 152 cm, 103 x 103 cm (framed)

Open Phone Booth is about the subversion of basic expressions of power. Communication is an articulation of power as it gives individuals agency, connectedness, and the state, by controlling the distribution of communication, claims this very territory. The body of work exposes that infrastructure is power and impersonates the very structure it is revealing by staging new forms infrastructures for the camera.

Self-Defloration

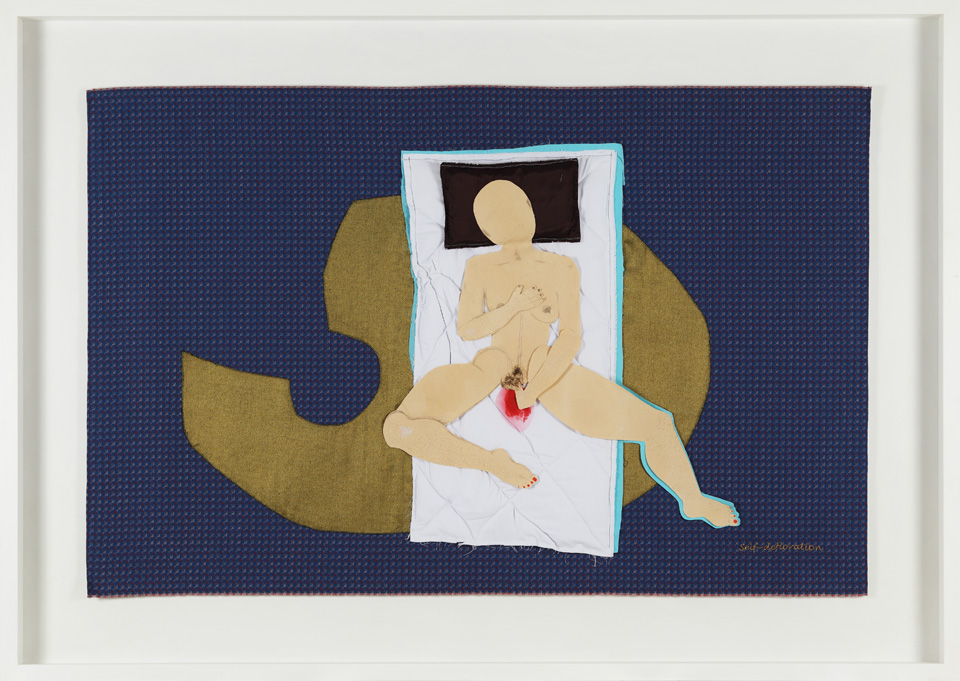

This portrayal of the villagers‘ self-empowerment is not dissimilar to an earlier, formative work by Güreş. Self-Defloration (2006) was an image of the woman’s self-empowerment. In a patriarchal culture in which the woman’s virginity is fetishized to the point of absurdity, „a“ woman—faceless and deformed, perhaps as a stand-in for all women and no woman—de-flowers herself.

The gush of blood has a violent connotation that is furthered by a subtle reference to self-mutilation, reflected in the woman’s form and the title of the work. The impetus for Open Phone Booth is comparable to Self-Defloration in that while the woman in Self-Defloration, by her eponymous act, claims power over her own body and life, the villagers that Güreş portrays in Open Phone Booth have found subtle ways of empowering themselves, en face with a state that selectively inclusive. The individual’s claim to self-govern is mirrored in the collective’s determination to self-sustain.

SELF-DEFLORATION, 2006

Mixed media on fabric, 193 x 270 cm (framed)

The slippage between the documentary and the fictional

The villagers exhibit an Antigone-like impetus and Güreş, in turn, mimics this impetus in her own constructed scenes. The slippage between the documentary and the fictional is quite essential in this body of work as Güreş proves that she has gone beyond observation and now partially embodies the very creativity, acceptance and defiance through action that the village breathes and lives every day. Antigone blurs the distinction between the state and the individual through the defiance of an individual of another individual, who is deemed the state. Open Phone Booth is the artist’s participation in a collective of individuals who fail to conform to the given order—lack thereof—by both passive resistance and the active act of living.

Nilbar Güreş’s practice holds a specific spot in the narration of contemporary art in Turkey as the artist’s works are seductively poetic, but are rooted in the social, cultural, and political issues that remain under-discussed. While her concerns and working methods are reminiscent of socially-engaged art, the consequent works are permeable. In other words, while Güreş makes very clear statements through her work, the rendition of these critical ideas is such that it is impossible to ever fully disagree with her. The use of humor is quite apt in that the artist both undermines and opens up her work to a wider reception through recognizing that many of the things that she is commenting on are daily, commonplace, and almost boring. Instead of glorifying her observations, she instead deeply entrenches these perceptions in what the viewer can recognize as the quotidian, no more, no less.

The artist’s positioning herself as an observer is also a conscious form of drawing the viewers into the work. Instead of looking from above or beyond, the artist is situated right next to the viewer and by mirroring the viewer’s own thoughts and own hesitations in figuring out whether what they are seeing is real or not, she also suggests that her criticality does not stem from a meticulously constructed, scholarly perspective, but rather things as they can be seen if only the daily was a little more twisted. The slight twist and the constant back and forth with between the documentary and constructed leaves the viewer with a satisfying confusion. If Güreş’s images are of what is there and what could be there, then the viewer can also create an imaginary space of what they could be doing—an alternative reality afforded by the artist’s slight of hands.

Creating a context for Güreş’s works—even within the framework of this article—requires thinking about the challenge of placing the works in a social, cultural, political, historical context, without stealing from their aesthetics. Or, to put it bluntly, is there a possibility of drowning the work of a woman artist from Turkey, due to the sheer appeal of their identity?

The answer to this question is perhaps two-fold. The first part is that Güreş’s works are very much rooted in the specific context that is both her home and site of inspiration. Knowing more about her context reveals deeper layers of meaning that might not have been possible without this knowledge. So, information is important when looking at the artist’s work.

However, the second part of the answer, is hidden in the inventive nature of Güreş’s work. In order for her works to survive in larger frameworks, perhaps unconsciously, perhaps consciously, Güreş has produced images and objects that not only speak to each other across projects and time, but also to the outside-of-Turkey viewers through their humanness.

In that sense, Güreş has happened upon a strategy to escape cultural stereotypes that the global art world seems to be more and more prone to by defying a linear narrative. From Trabzon, where her mother is from, she has moved onto Bingöl; while both of the projects utilize photography and both are superficially related in that the two places are familiar to Güreş since childhood, she played completely different roles. The fictional scenes produced in the very specific landscape of the Black Sea Region are in clear contrast to the social researcher, innovator between the different media employed to represent the Open Phone Booth at a remote village in Bingöl. As Güreş disrupts her own narrative, one can’t help but wonder about the potentialities liberated by multiple narratives in an artist’s practice.