DARE guest author Toby Kamps met with the artist Noémi Barbaglia in her exhibition The Hallway at Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof. In his review he places her work in the context of artistic discourses on space and light, becoming and passing away

Noémi Barbaglia, The Hallway, 2024, Ausstellungsansicht, Foto: Fred Dott

A first-time visitor to the Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof and Noémi Barbaglia’s large-scale installation there, The Hallway, might miss it. They may stroll down the eponymous corridor, expecting to visit an exhibition of the sculptures made of fiberglass, paint, and other materials that have made her a standout new talent in Hamburg. This is understandable. Calling to mind otherworldly life forms and ghostly fragments from domestic interiors, Barbaglia’s previous works combine abstract, biomorphic shapes and various forms of representation, from trompe l’ œil realism to spectral casts of real-world objects. The Hallway is an architectural environment made of conventional building materials that, as it collapses art and architecture in one experience, calls little attention to itself. Instead, it feels like one of the countless corporate or institutional corridors to which so many of us have been condemned to wander or wait. It is a dramatic change in direction for the artist—a move she modestly calls “another gesture . . . another image.” Yet in its slow-burning, associative approach, it has more in common with the artist’s other work than meets the eye.

Noémi Barbaglia, The Hallway, 2024, Ausstellungsansicht, Foto: Fred Dott

Spanning the length of the Kunstverein, from its glass doors to its back-of-house bar (currently fitted out with a delightfully loopy installation by Stella Rossié), The Hallway is 20 meters long, 8 meters high, and just over 2 meters wide. Open at the top, it is made of white-painted drywall and features 18 frosted windows set at regular intervals in narrow vertical alcoves. It obscures almost all of the regular exhibition space, a former first-class waiting room from 1879 fitted with ornate architectural moldings and coffered ceilings, as well as the more recent metal ramp leading into it.

Noémi Barbaglia at The Hallway, 2024, Foto: Toby Kamps

At the end of the work, you find yourself in an awkward, nearly square room made from a short, right-angle continuation of the work’s windowed walls and a corner of the room’s original architecture. It is in this space that the uninformed visitor might begin the search for the sense of the work, combing memory and experience for interpretive toeholds. This process links The Hallway to Barbaglia’s sculptures. She says that many who have followed her career tell her that “something hovers over the work,” that their forms trail clouds of mysteries and associations. Indeed, the more time one spends in The Hallway, the more one has the feeling that the work is more about transporting the viewer to a different state of awareness than delivering any specific message.

Noémi Barbaglia at her studio, 2024, Foto: Toby Kamps

Barbaglia who was born in Luxemburg in 1993 and graduated from Hochschule für bildende Künste (HFBK), Hamburg’s Academy of Fine Arts, in 2022 is not interested in easy answers. Deeply engaged with a broad range of subjects, from poetry and literary theory to gender studies to sociology, she works as an artist because it allows her to move between disciplines. Writing, she says, is a daily activity that runs alongside her sculptural practice as another means to develop ideas and forms, although she says it is never specifically “about” what she is making. In fact, the ways we learn things interest her more than the things we know. The studio’s hands-on processes are the means by which she translates the act of discovery into expression. “That’s why I work,” she says. “As my interests coalesce, a certain nebulosity arises, but then I think and research through the fog and the connections between things get clearer, come together, and complete themselves.” Her signature material fiberglass also enables her to access different dimensions. It can be opaque or transparent, solid or gossamer, and she can use it in ways that are both painterly and sculptural.

Noémi Barbaglia, The Hallway, 2024, Ausstellungsansicht, Foto: Fred Dott

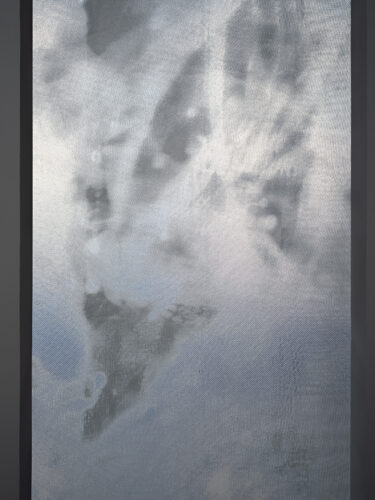

The Hallway’s windows are made of thin panels of fiberglass on which their strengthening resin applied in a painterly, scrambled fashion. This lends them differing degrees of transparency and translucency and gives the natural light from the Kunstverein’s exterior windows coming through them a variegated effect. Some patches glow hot white while others allow the colors of the sky to seep through. This injection of the painterly and hand-worked undercuts the otherwise uninflected procession the spare corridor. It lends the structure a slightly defunct quality reminiscent of the soaped-over panes of empty storefronts. As the daylight pervading the space gradually changes, one thinks of the visual-perception investigations of American Light and Space artists like James Turrell and Robert Irwin. The faint sounds of train brakes and whistles filtering into the work from the busy platforms below, however, inspire more universal meditations on the passage of time.

„o.t.“, 2021, Foto: Helge Mundt

A certain Ambiguitätsverhältnis, or comfort with ambiguity, is a prerequisite for Barbaglia. Mixing materials and oftentimes metaphors, all of her sculptures contain multiple layers of signification and are suffused with mystery and a sense of play. The floor-mounted sculpture o.t. (2021), for example, is a conical structure made of two conjoined mats of fiberglass. Parts of each sheet are infused with resin and molded in their middles into a bell like form, while parts of the surrounding flanges a left untreated and hang limply. Stacks of small magnets suggesting a bolts, bicycle tire valves, or chess pieces stud the work, holding its halves together and lending the whole a cyborgian air—as if it were part beached seashell, part crashed spaceship. Displayed in an exhibition in Hamburg’s Michaeliskirche in 2022, this ghostlike form suggested a via negativa like that described by Susan Sontag in her 1967 essay “The Aesthetics of Silence“, “a craving for the cloud of unknowing beyond knowledge.”(1)

„Serious Seduction II“ (Detail), 2022, Foto: Conrad Hübbe

Another series of works inspired by windows complicates ideas of interior and exterior—in both architecture and psychology. Serious Seduction II (2022) is cast from the left half of an arched window, as if a sheet had been blown by rain and wind against its mullions. A sinuous lick of purple-blue paint runs up the left side, disappearing under a fold of hanging cloth. One could imagine spying a backlighted human form against it at night. One could also imagine the itching-powder feel of brushing up against the loose fibers that dangle from its fringes. Pronounced in this sculpture, the motif of the veil recurs in Barbaglia’s work because of its intermediary function—as a boundary between inside and outside, appearance and reality, life and death. She notes that it can be an attribute of women at milestones in their lives, like marriage or widowhood, as she notes that the 18 windows in The Hallway mark the passage from childhood to adulthood.

„Permanent View“, 2022, Foto: Volker Renner

Cast from a convex rooftop skylight, the floor-mounted sculpture Permanent View (2022) has a distinctly tomblike aspect. Its upward-swelling form recalls a freshly dug grave while its draped white resin-infused cloth suggests a burial shroud. Its title points to the fable of Snow White as well as the actual stories of Lenin and Mao, whose bodies were displayed in transparent coffins. This funeral feeling is also present in The Hallway, which in its unhurried stateliness, has something in common with the white marble mausolea and their vertical stacks of crypts. Like British artist Rachel Whiteread’s concrete casts of the interiors of derelict houses, Permanent View materializes a void to create a powerful “today me, tomorrow you” memento mori.

„Discloth“, 2023, Foto: Helge Mundt

Other works engage in giddy play with ideas of construction and deconstruction. Dishcloth (2023) renders the most utilitarian of household objects useless. A piece of white fiberglass mat, its edges silkscreened with Mother-Teresa blue stripes, is dipped in resin so that it frozen forever in a casual drape. And Bürden (Burden) (2020) combines metal and wooden slats, magnets, fiberglass, carbon fiber, postage stamps, rattan, and adhesive fabric in the approximate form of a sawhorse to enact an absurd and precarious battle of form and function. Like the “eccentric abstraction” experiments in fiberglass of American artists Eva Hesse and Bruce Nauman, Barbaglia’s work conflates aspects of conceptual art and Surrealism in objects that are as uncanny and inventive as they are cerebral and searching.

Noémi Barbaglia, The Hallway, 2024, Ausstellungsansicht, Foto: Fred Dott

The invitation to exhibit The Hallway in the Harburger Bahnhof, Barbaglia’s first institutional project, came from the Kunstverein’s director Tobias Peper who saw in her work expressions of the idea of the heterotopia. Invented by French philosopher Michel Foucault, this term refers to a category of places removed from everyday life such as museums, cemeteries, gardens, brothels, and Muslim baths that both mirror and unsettle the social setting in which they exist. It was, Peper believed, an apt description of his institution, a free-of-charge site of free cultural experimentation in the heart of a busy transport node in a working-class quarter of Hamburg. The Kunstverein, like all heterotopias, is a place of “otherness” at odds with its environment that contradicts, disrupts, and transforms the everyday flow of experience.

Tobias Peper und Noémi Barbaglia, Foto: Toby Kamps

Indeed, The Hallway is a world within a world within a world. Standing in it, one cannot help but compile a cloud of questions and associations. Just as Barbaglia did when she conceived of it, we must draw on our acquired knowledge and bodily sensoria in order to contemplate it. Is it set design, a conjuration of some of the institutional corridors in which we spend so much of our lives in limbo? Is it an echo of modernist interpretations of classical architecture like painter Giorgio de Chirico’s light-struck colonnades? Is it a young artist’s memorial to her past life in the halls of academia? Perhaps it is all of these and something more universal: a conveyance to those indeterminate states of mind in which we open ourselves to mysteries of life and experience.

(1) Susan Sontag, „The Aesthetices of Silence“ (1967), in Styles of Radical Will (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1969), pp. 4-5

Noémi Barbaglia at The Hallway, 2024, Foto: Toby Kamps

Auf einen Blick:

Ausstellung: Noémi Barbaglia – The Hallway

Ort: Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof

Zeit: bis 25.8.2024, Mi-So 14-18 Uhr, Mo und Di geschlossen

Internet: www.kvbf.de

Noémi Barbaglia at her studio, 2024, Foto: Toby Kamps