Hamburg based photographer Axel Beyer is looking for the quiet enigmas in the ordinary

Stadt Räume – Hamburg 1983 – 1987, Axel Beyer’s exhibition of photographs of his city’s workaday streets has the quality of a dream. Made with a high-resolution medium-format film camera as his graduate project for the Fachhochschule für Gestaltung nearly 40 years ago and exhibited this summer at St. Pauli’s Hamburg Werkstatt Fotografie (HWF), the images document a vanished world.

Axel Beyer: Stadt Raum, 1983-1987 © Axel Beyer

An inspiration for the works, the trim, bright-eyed sixty-something artist says, was the American New Topographics movement. In the mid-1970s, Stephen Shore, Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, and other photographers began to document everyday built and natural landscapes. Aiming for a cool, apprising neutrality, they studied everyday urban and suburban environments while avoiding the human subject and overtly critical viewpoints. Wilhelm Schürmann who worked in a similar vein in Germany, Beyer says, was another impetus for him to move beyond his early figure-focused “magic realist” style.

Axel Beyer outside Hamburg Werkstatt Fotografie (HWF), photo: Toby Kamps

Life’s mysteries, of course, still haunted these earlier chroniclers of the roadside vernacular as they do all photographers. This is because the medium, for all its mechanical matter-of-factness, always partakes of the uncanny. By freezing a moment from the evanescent flow of time, it reveals wonders, complex and mundane, that escape real-time perception. In his studies of the modern world’s terrains, Beyer, like his predecessors, exposes the magic and beauty in the city’s forgotten corners and everyday non-places.

Axel Beyer: Stadt Raum, 1983-1987 © Axel Beyer

Comprised of vacant lots, shop windows, construction-site fences, and walled-off forecourts, most shot in flat daylight, Beyer’s photographs are saturated with information and ambiance. They show the Hamburg we all know: a city of straight, wide streets, nice cars, and parked campers in which order and disarray continuously tussle. The pale yellow, off-white, and beige buildings filling his pictures are also familiar to anyone who has traversed the North-German metropolis. Yet his carefully composed images from a just-out-of-reach past conjure a strange mirror-world, one in which things vibrate at a different frequency.

Axel Beyer: Stadt Raum, 1983-1987 © Axel Beyer

In this sense, Beyer’s studies of the poetics of light, architectural space, and perspective call to mind Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico’s “Metaphysical School” paintings of the 1910s. Influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche’s search for the deeper logic underlying the realm of sensations, de Chirico imagined empty, arcade-edged piazzas suffused with mystery and stillness. Beyer’s color film and digital print medium and parking lot subject matter are from another time and place, but the search for the quiet enigmas in the ordinary is the same.

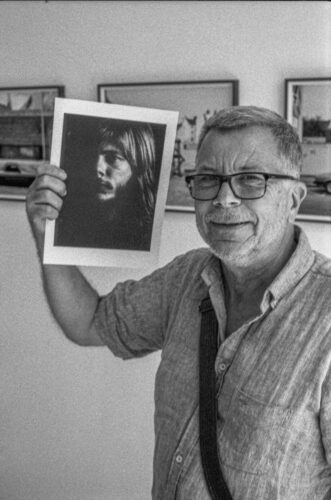

Portrait Axel Beyer, photo: Toby Kamps

Michael Grieve, founder of the HWF, immediately recognized Stadt Räume’s documentary and nostalgic power. Introduced to the work by British photographer Mark Power, whose course Beyer attended at the workshop, Grieve was excited to exhibit it publicly for the first time, noting that “there’s an incredible lack of restriction in his scenes. There are almost no street signs, the world seems free and open and you are alone in it.” To anyone who had a driver’s license in the 1980s, this writer included, the photographs bring to life a bygone, gasoline-perfumed era – one in which it never seemed to take long to drive to a destination or difficult to park up in front of it.

Axel Beyer: Stadt Raum, 1983-1987 © Axel Beyer

Beyer himself is astonished by what he sees in Stadt Räume. He notes that, in comparison with today’s traffic-clogged city, there are scarcely any cars in the images. The colors of the vehicles themselves are also dramatically different. Baby blue, caramel brown, and emerald green Volkswagens and Fords perch on sobersided gray streets like vintage parakeets. And the graffiti that lends such visual noise to Hamburg today is almost entirely absent, lending the scenes a preternatural stillness. It is, however, Beyer’s knack for discovering the metaphysics in the most mundane precincts, that gives his work its transcendent power.

Axel Beyer taking photographs, photo: Toby Kamps

This sympathy for urban sprawl’s sublime geometries, Beyer speculates, may stem from childhood experiments with photography. Inspired by Harald Mante’s famous books on color and composition in photography from the 1970s and 80s, he describes using the Canon AE1 he received as a confirmation present to transform the crop rows near his grandfather’s country house near Lüneburg into “graphic, reductive” designs: “I was always curious to see how something would look as a photograph.” Established early, this incisive vision, at once mapping and abstracting, continue to guide his work. Today, Beyer works in a variety of experimental, open-ended modes. He makes images investigating and oftentimes constructing intersections of form and content.

Axel Beyer: Bebra, 2009-2010 © Axel Beyer

Bebra Curiosa, which in book form won a pre-publication award at the 2010 Photo Book Festival in Kassel, consists of digitally collaged architectural images taken in the titular city in Hessen, a rail hub whose fortunes declined after German reunification. From the first of his many visits to his late wife’s family there, Beyer felt compelled to explore the “Bebraistic Cosmos,” its careworn half-timber houses, abandoned commercial buildings, and claustrophobic streets. Using the computer image manipulation skills he honed as a longtime photo editor for Sport Bild, he reconfigures aspects of the city in eerie mise-en-abime montages. In these pictures within pictures, in which perspectives are carefully aligned to suggest plausible physical spaces, rows of suburban houses fill empty department stores, tiny dwellings sit on tables in wallpapered kitchens, and all manner of interiors and exteriors interpenetrate each other, confounding ideas of inside and outside, real and unreal. They are tragicomic dollhouses and funhouse mirrors for a deindustrialized world.

Axel Beyer: Kali Mania, 2011-2017 © Axel Beyer

Other series study the built world’s curiosities, clashes, and artifices, pushing to find ever more layers and estrangements from ordinary experience. Begun In the late 1980s and still in progress, „Insomnia“ consists of close-up, corner-of-the-eye fragments grabbed on the move: hotel-room corners, desktops, and museum displays, many of the latter collected in former East Germany. It hints at unsettling shifts in consciousness after the Fall of the Berlin Wall that continue to play out in the country’s politics. Kali Mania, another series drawn from the Hessian landscape, documents the giant mountain of potassium-mine tailings near Heringen. Glimpsed over backyard fences and at the end of go-nowhere streets, the towering mountain of industrial waste memorializes an unsustainable way of life. Świnoujście considers the harbor town at the Polish tip of the island Usedom, where socialist and traditional architecture mix. Focusing on weatherbeaten walls and shop windows, these “straight” unmanipulated images depict fascinating interplays of light, shadow, and history.

Axel Beyer: Swinoujscie, 2018 © Axel Beyer

The project Unreal Estate, winner of a 2020 Vonovia Award for Photography, is a recent standout among the work derived from Beyer’s ongoing engagement with Hamburg. In straight and digitally montaged images, it considers the countless new-build housing projects popping up throughout the city and the giant trade fairs at which their high-tech construction materials are promoted. As suggested by their names, such as “Pergola Quarter” or “Cascade Park,” these complexes of compact, geometric structures reflect the dream of a perfect urban perch, a home balanced between organic and constructed realms. These structures, however, express mainly the rigid logic of their efficient designs and materials, leaving little room for any of nature’s wildness. Through myriad details, such as tiny gravel gardens glimpsed through fences bedecked with plastic leaves, Beyer highlights their claustrophobic, dystopian aspects.

Axel Beyer: Unreal Estate, 2018-2022 © Axel Beyer

Today, as a relentlessly expanding Hamburg often feels like a giant construction site, Beyer’s Stadt Räume project continues apace, and he is beginning new projects studying cityscapes in the Baltic countries and the strange juxtapositions office furniture found in Sozialkaufhäuser, or social department stores. Following Beyer as he pedals his camera-carrying electric bicycle through the city in search of new images is to see an artist alive to a place’s energies. From his smile and the bounce in his step as he discovers a new subject, it is clear he has never lost a childlike amazement at the world’s wonders. When pressed about his evergreen capacity for amazement, he admits that it might stem from the hours he spent building models as a child. Being able to envision one’s surroundings in miniature, as a diorama in which each detail is precious, he imagines, was good training for his photographic projects. “The landscape is a puzzle for me,” the artist says. “And I try to be completely open to everything it has to offer.”

Axel Beyer: Stand der Dinge (Sozialkaufhäuser), 2022-2024 © Axel Beyer

www.axelbeyer.de

www.hamburgwerkstattfotografie.com/exhibitions

Axel Beyer with 1980s portrait, photo: Toby Kamps