DARE guest author Toby Kamps met with Fabien Lübke and his partner Elias Langermann in Hamburg

Fabien Lübke, Photo: Toby Kamps

“I am a story that tells itself,” says Fabien Lübke who, along with his partner Elias Langermann, transmutes life into art in diaristic and dreamlike videos. Working in a rough-hewn, self-documenting mode, Lübke and Langermann, both 26, discover the magic that can reveal itself in the everyday—in drunken embraces, urban adventures, or games invented with friends. By paying close attention to the world and their places in it, the two have distinguished themselves as some of Hamburg’s most original and exciting emerging artists.

Like many of their contemporaries using digital video and sound recording devices to navigate an intensely online cultural moment, Lübke and Langermann wade through avalanches of real and screen-based information. Yet their work cuts through this alienating overload to connect with the timeless idea of the Romantic quest, of searching for intense feelings and connection with the wonders that surround us. Built on the propulsive power of creative friendships and a search for awe in the everyday, their work feels disarmingly fresh and integrative.

Graduation at HFBK, Photo: Fabien Lübke

Tall, round-faced, and glowing with affable energy and a Kerouacian drive to talk, often in German and English in the same sentence, Lübke, like Langermann, is an urban forager—in life and art. In January 2024, he met to discuss this article in an abandoned apartment in Altona still filled with the previous owner’s detritus. His wardrobe, which he combines in outfits ranging from nonbinary and vaguely druidic to cisgendered and mismatched-louche, comes from street and giveaway-shelf finds. And much of his food is salvaged from restaurant leftovers. This same appreciation for the treasures permeating the modern world shines through in the videos and stems, Lübke says, from the duo’s free-ranging and experimental teenage years in Munich.

Elias Langermann, Photo: Fabien Lübke

Lübke and Langermann met when they were both around 15. Lübke was hanging out in that city’s outskirts and spending much of his time looking for weed. He describes how he would regularly get into uncomfortable situations during his frantic searches, while Langermann would simply walk around and chat with people, likely finding something without looking. “Elias was the coolest, sexiest, most laisser-faire person in Munich to me,” Lübke recalls. “With him finding the perfect place to light a joint replaced actually smoking one.” By chance, both he and Langermann brought skeins of wool to their first hangout and used them to make street-art. From then on, games became an important part of their relationship and artistic process. Concocted from anything—outrageous dares, impromptu spoken-word performances, trying to trick internet search engines—their pastimes became a collaborative means to harness the creative power of loose, associative thinking. Today, Lübke compares himself to Obelix, the comic-book Gaul whose superpowers came from falling into a vat of magic potion as a baby, claiming that he smoked so much weed as a teen that he no longer needs it to access freeform imagination or release himself from society’s strictures. Yet games remain at the heart of the vision he shares with Langermann: that life is an invitation to play.

Exit Spiele Kosmos, Still, Photo: Courtesy Fabien Lübke and Elias Langermann

The videos, which Lübke calls “Diary-Films,” stem from an early sense that the time he spent with Langermann was worth commemorating. Running wild in they city, the pair and their friends made countless photographs and videos of each other and the things they encountered on their extralegal explorations. “Elias showed me how to be outside,” says Lübke. “He showed me how to keep moving to stay warm on cold nights and also how to be patient.” Calling it “dazuhocken,” or sitting with something, the artists have made patience and endurance central to their approach. Whether getting busted as teens by the police and spending long nights at the station, going undercover at a Check24 Christmas party until the boss kicks them out because he has told them too much, or sitting on a bedroom on a blazing hot afternoon working on the perfect sound loop like those Lübke uses in his rap performances, they work to stay with experiences to find the inspirations in them.

Fabien Lübke, Photo: Toby Kamps

This unhurried, investigative energy drives the 2022 film Die Langeweile der Jugend (The Boredom of Youth). It stars the Austrian actor Petra Morzé, whom Lübke met at a screening of one of her films in Vienna and reconnected with through her daughter, who became a friend at Hamburg’s Academy for Fine Arts, where he studies. Recording in ghostly green low light mode, the camera tracks Morzé as she wanders through a Munich night reading aloud from Lübke’s diary. She does what Lübke and Langermann did as teens: smoke in playground huts, eat at McDonald’s, build fires from scrap wood, and fish with improvised pole and hook. The arc of dramatic tension in the work, Lübke notes, is largely flat. He does not aim for catharsis or resolution—only, he hopes, the “slight trembling” that comes from “a sublime that I can be part of or that can be part of me.” At the end of the film, Morzé drags a giant fallen branch up the stairs to Langermann’s parents’ apartment. There, the film switches to color and, as Hamburg writer and publisher Nora Sdun notes, a “shocking normality” reigns. But then a television is switched on to a broadcast of fireworks in a night sky, and the dream continues.

Graduation at HFBK, Photo: Fabien Lübke

The 2023 film Exit Spiele Kosmos pushes this wandering, observational approach to cosmic scale. The work is a 55-minute compilation of dozens of disparate scenes collected from the artists’ wanderings and sittings-withs, some shot with handheld cameras, others grabbed from computer screens. Together these fragments suggest a grand, at times hallucinatory narrative of scavenging, communal play, solitary creative work, and unending curiosity. Among them are shots of Lübke dressing himself in clothing found in the abandoned apartment next door and vomiting in the arms of a friend; Langermann falling asleep in a concert-hall balcony; a woman mixing and spitting in a giant vat of dough; and men and women studying the contents of trash cans in a dump.

Exit Spiele Kosmos, Still, Photo: Courtesy Fabien Lübke and Elias Langermann

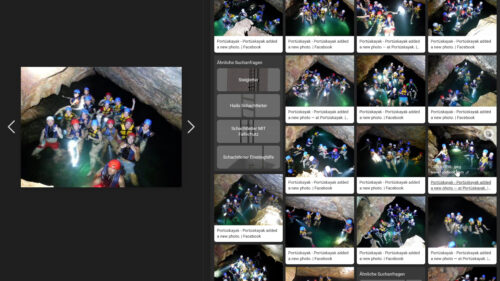

Interspersed throughout are screen-captures from the game that inspired with work’s title and structure, “Bing Bingo,” invented from the internet search engine Bing. Players try to trick the program’s picture-matching algorhythm by choosing the least similar image from dozens of nearly identical images in order to jump from one category to another. For example, clicking on an image from the category toast might take you to a loaf of whole-grain bread, which could lead to a bakery, which could lead to a restaurant. Of course, there is no exit and no escape. Each move is a link in a near-infinite chain of associations and adjacencies, and they spark new thoughts and feeling as we try to connect them. One protracted scene of rapid-fire image-clicking, of switching picture of swimmers, spelunkers, sports teams, and kindergarten classes spotlights the wooziness that comes from online life’s rapid context switching. But then a swelling choir of male and female voices rises to softly sing the question “How did I get here?” and we cannot help but feel amazed at all that life—and the internet—can serve up for us.

Fabien Lübke and Elias Langermann, Photo: Fabien Lübke

Playing over the film’s diegetic sounds, a voiceover recitation, in Lübke’s perfectly enunciated German, of childhood memories, philosophical musings, and snippets of surreal poetry ties these disparate visions together and lends the whole a driving force. This structure calls to mind the films of Jonas Mekas, a Lithuanian-born American filmmaker who is an important influence for the artists. Beginning in the 1960s, Mekas used the movie camera to snatch fragments from life spent with family and friends and tied them together with music and spoken texts to meditate on the passing of time. Exit Spiele Kosmos, updates this format for a time when images and ideas travel at the speed of light and for artists reaching for the infinite. As the jury that awarded it the Hamburg Academy of Fine Arts’ Karl H. Ditze prize for the best bachelor-degree diploma project noted, “The exceptional intensity and exuberant opulence of this work captivates the audience and allows them to participate in an extraordinary existence.”

Fabien Lübke, Photo: Toby Kamps

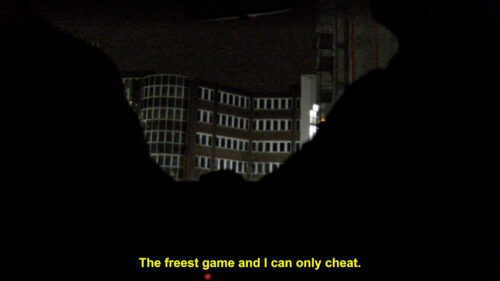

Toward the middle of the film, in what might count as a mini-crescendo in its intentionally flat dramatic arc, a sense of being on a journey begins to coalesce. We find ourselves in the back seat of a car moving through a rainy city night while freestyle rap plays. Made by the artists and friends by passing an iPhone between them, it is a kind of spoken-word exquisite corpse: “. . . dental floss threads through the air / Aquamarine the sky, weighs a pound / The freest game and I can only cheat.” After that, we land in a torchlit nighttime procession—Sylt’s Biikebrennen, a bonfire night held to mark the end of winter with pagan roots. As they convey us through these and the film’s myriad experiences, Lübke and Langermann illustrate their belief that the universe is unfolding exactly as it should and that marvels abound in every moment.

This faith in life’s unending game of existential pinball recently has sent the artists on their next immersive adventure. Late last year, Lübke spilled coffee on himself when his cab braked suddenly. The driver felt so bad that he insisted on giving him a clean t-shirt emblazoned with “Tanzania.” This sign, along with the driver’s recommendation that it was a great country to visit, inspired to Lübke and Langermann to fly to Dar es Salaam in late February 2024. Following their belief in “opening doors,” of pushing to explore any intriguing situation, they are updating the notion of the Romantic quest for the digital age. They are diving into a new realm and trusting that they will find more of what fuels their work: fellowship, imagination, feeling, and transcendence.

Deformed camera, Photo: Toby Kamps